A review of Sam Kieth’s Arkham Asylum: Madness.

Ever wondered what it might be like to work at Arkham Asylum? Who on Earth would be willing to work with the most violent and deprived criminals? This is a side of things that Sam Kieth (The Maxx, Zero Girl, Sandman) explores in his story Arkham Asylum: Madness, both written and illustrated by him.

As expected, the story takes place in the asylum,and despite the narrations from a variety of characters the story focuses on a woman called Sabine, and there is no Batman in sight. Sabine is one of the staff charged with the care of the residents of Arkham – a daunting task indeed.

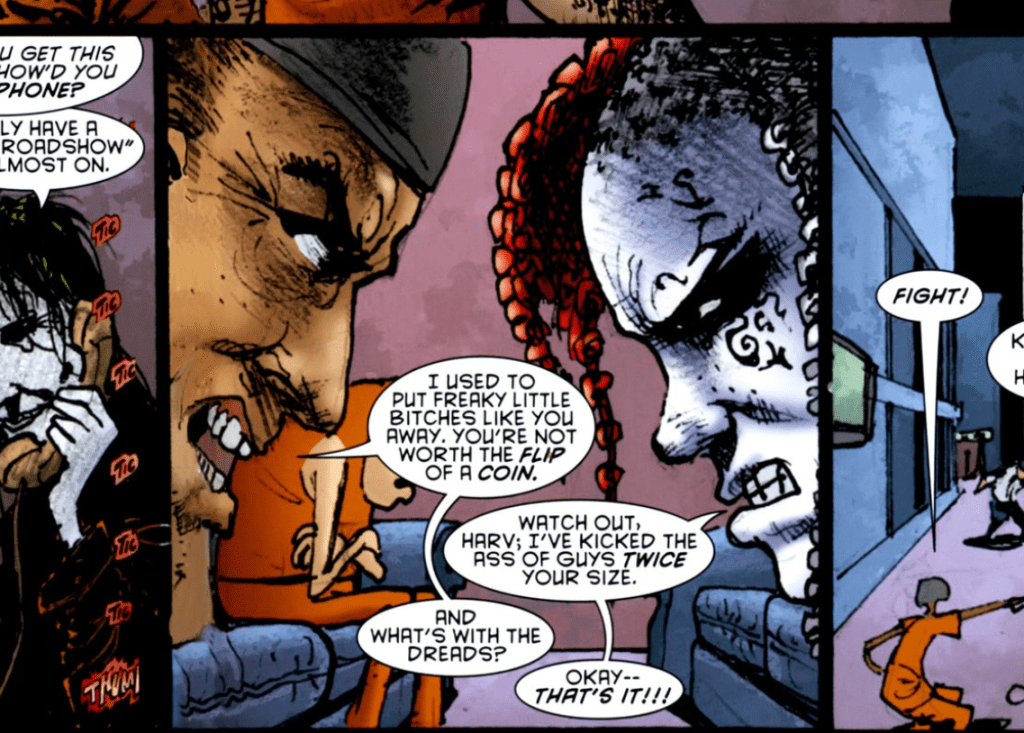

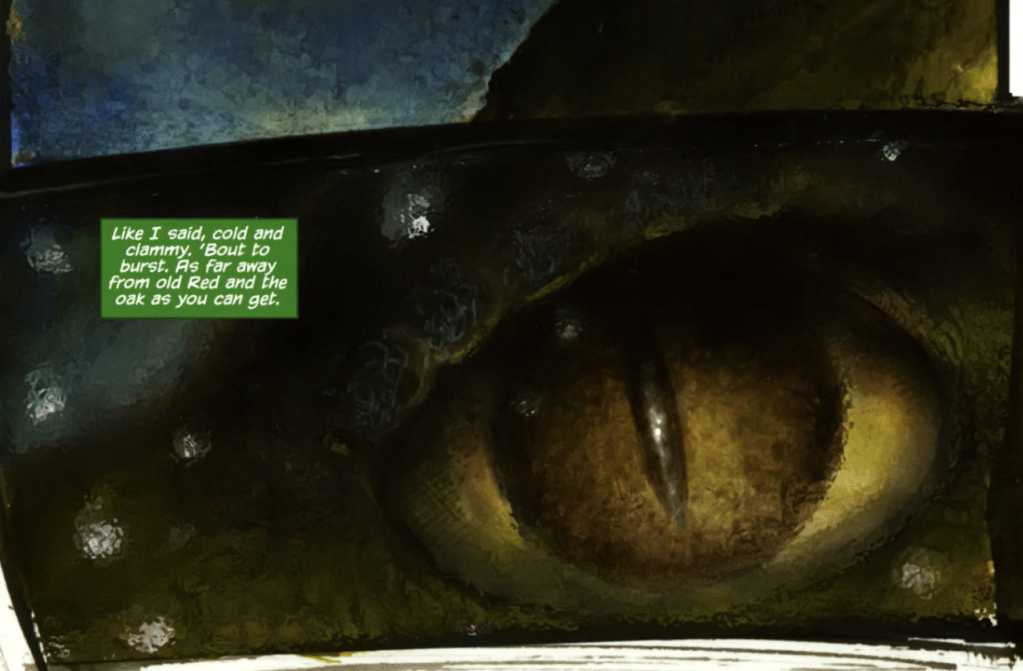

We follow a full 24-hour cycle in the Asylum as Sabine’s day shift gets extended into a night shift as well. The tension builds as time progresses as we are introduced to the inhabitants. Harley squares off with Harvey, Killer Croc’s tank puts a strain on the entire building and Joker is up to something.

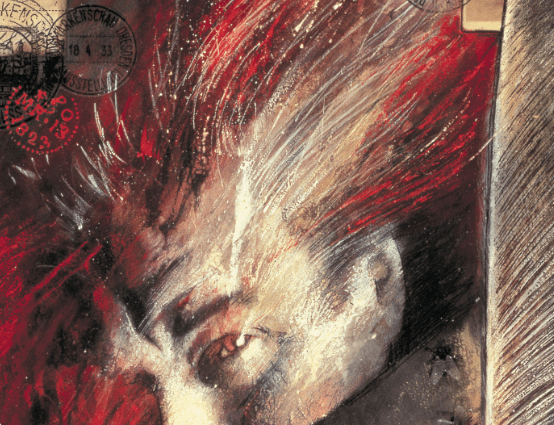

Kieth’s art style is not for everyone and in this story it gives some contrasting panels. There are some with interesting proportions, others with playful clothing and some that would not feel out of place in McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth. What it does do is add a real sense of delirium and madness to the comic.

Kieth also has some interesting takes on the incarcerated villains. Croc is absolutely terrifying and leads to the question – why is he in the Asylum and not a prison for the super powered? Kieth’s versions of Harley Quinn and Two-Face feel a bit odd visually, but you can make up your own minds on that.

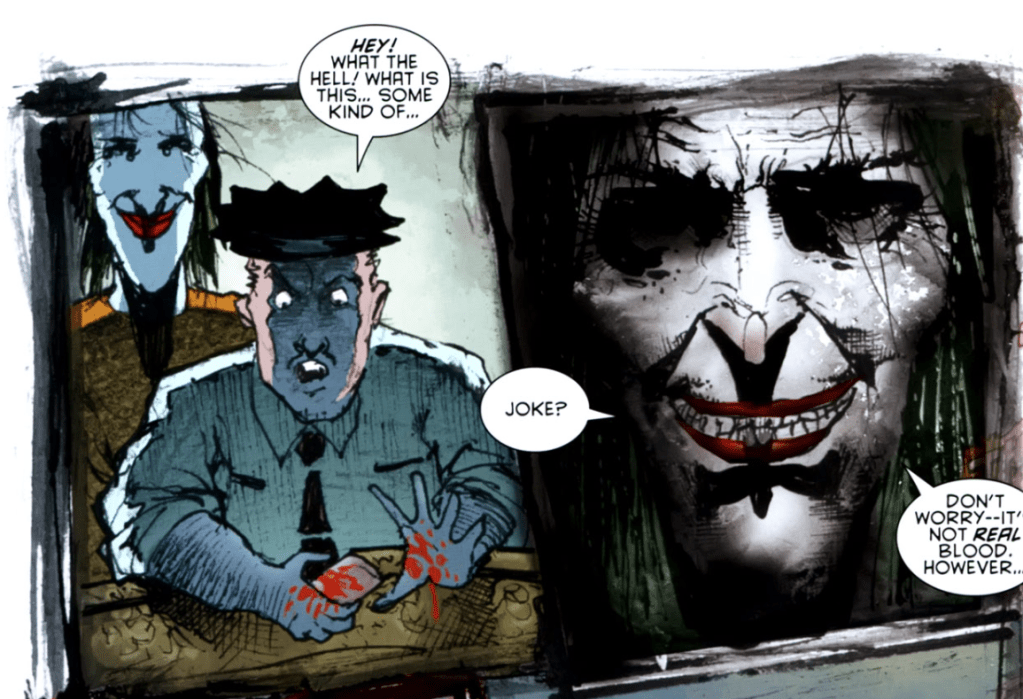

What does stand out is Kieth’s Joker who maintains the balance of being incredibly scary but maintaining a sense of dark whimsy too. All of Joker’s acts of violence revolve around practical parlour trinkets, like the arrow through the head joke or soap that turns into blood. There is no edginess for the sake of edginess here.

At the heart of the story is a ticking clock, which Keith uses to both push the narrative along but also direct the characters’ emotional state. On one hand, the noise of the clock and the eventual blood dripping down it are horrifying to the staff and the reader. There is a sense that something supernatural is happening and the clock is counting down to something terrible. Not the most original idea in comics but still, it adds apprehension.

On the flip side, the clock adds complete and utter mundanity to the story. The clock is a key point of reference to all staff, most of whom are there on a shift basis. Clocks say when it’s time for a break. They also mark the end of shifts, a time for some, like Sabine, to get home to loved ones, to escape, and, frankly, to mark another day surviving.

The staff working there are not there out of any sense of duty to rehabilitate the inmates or for their professional progression. Instead, the staff are there for the reason most people work. To get paid. To pay for food. For schooling. For rent. This is not to say staff do not know who is housed in the asylum – Sabine’s son asks her outright. A job is a job though and for those with little choice, they have to work it.

Like any other place of work, there is politics, romance, grievances, and even that one person who you never know their name. Kieth weaves all of this really well into the story as staff sneak off to have sex, Sabine argues with Reed about finishing early, and the guards take revenge on Joker by beating him.

Even here, a place of work you’d expect to bring about a real sense of camaraderie, there is a two tiered system. Working there is horrible, but working there at night is much worse. No one wants to work there at night but are forced to through superiors and circumstances. The day shift would even leave tasks for the night shift to do. Sabine notices that things are even more on edge at night, with staff barely talking to each other and just counting down the minutes until sunrise.

Ultimately the madness peaks at 4am, with Croc’s tank bursting. Joker foresaw this, due to the Asylum’s old waterworks, but kept things balanced by not removing his jaw restraints. As for the clock, a mouse had died in it, causing the issues. In such a stressful environment, such a little thing had produced incredible stress among the staff.

Despite the chaos, all staff and inmates remained at Arkham. No villains escaped and resignation letters, including from Sabine, were penned but not sent. For the villains, leaving was not an option as Arkham is their home. Could the same be said of the staff? Sabine confides to her son that it is him that gets her through the day.

Ultimately, Kieth’s story is an interesting one, but does not feel that polished. His exploration of those who work at Arkham is refreshing, as outside of the occasional doctor or psychologist, they are mainly ignored. Arkham’s staff in most comics feel as faceless as if they were members of A.I.M. or the Hand.

The artwork is definitely interesting. Kieth is probably his own worst critic, saying his use of watercolours with digital work and photography does not achieve what he had hoped it would. However, it lends itself to a shifting experience when reading which makes sense for a comic about Arkham. And Kieth should be commended for the extra work he went to in making Joker’s parlour tricks and photographing them.

The payoff at the end as well is perhaps not what it could be, feeling a bit of a letdown. Kieth designs a really menacing Killer Croc and it would have been great to see him wrecking the place, but obviously that is not the point of the story. It is about what people do to get through the day, even in the worst working environments.

Leave a comment